Rivals: how the power struggle between China, India and Japan will shape our next decade

Bill EmmottAllen Lane, £20Tablet bookshop

price £18 Tel 01420 592974

China and India are invoked as bogeys by British politicians seeking to persuade the public that the economy must become more competitive to survive in an age of globalisation.

The two fast-growing Asian giants are also seen as ominous contributors to climate change. They have come to impinge on British consciousness in an unprecedented way.

Thirty years ago, Japan occupied a comparable position. That was the age of investment by consumer electronic companies such as Sony and Matsushita, which were followed by car-makers and other large-scale manufacturers. Management techniques such as a common canteen for bosses and workers, "quality circles" and just-in-time ordering were held up as models to a domestic industry in dire straits.

Lessons were learnt but then Japan faded from public view as the stock - and property-market - bubbles burst and the country entered a decade of stagnation. Yet its economy remained the second largest in the world, after the United States, and since 2002 it has been recovering. The rapid switch from emulation to oblivion always seemed artificial.

It is the merit of Bill Emmott's book that he brackets these three Asian powers not just as dominant players in their own continent but as certain to have a profound global impact over the next 10 years - thus the inflated subtitle of his book. The rise, first of Japan, then of China and India, he argues, is creating a market for goods, services and capital running from Tokyo to Tehran. This will form "the single biggest and most beneficial economic development in the twenty-first century, providing dynamism, trade, technological innovation and growth that will help us all".

However, as the subtitle also indicates, such progress could be blown off course by clashing interests. Emmott compares the emergence of three power centres in Asia with rivalry between Austria, Britain, France, Germany and Russia in the nineteenth century. That culminated in two world wars. Since then, however, Europe has sought to put conflict behind it through economic and political integration. The foundation for this process was reconciliation between France and West Germany.

In Asia, by contrast, the scars of the past, whether Japanese military atrocities or India's drubbing by China in the border war of 1962, are still livid. And the structures for handling tension remain embryonic; compare them with the Helsinki Process during the Cold War and the subsequent creation of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe.

Rivals opens with praise for George W. Bush for putting ties with the world's most populous democracy, India, on a completely new footing. Rapprochement began after the nuclear tests of 1998 and resulted in the first presidential visit to New Delhi, by Bill Clinton, in 22 years. In 2006 Mr Bush went much further than his predecessor by agreeing to collaborate over civil nuclear energy, despite the fact that India had not signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Emmott sees this strategic partnership as a prime example of great-power manoeuvring, the purpose in this case being to limit the influence of China.

All three countries are devoting huge resources to defence. Last year China demonstrated its new capabilities by destroying one of its weather satellites with a surface-to-air missile; India is refurbishing or building aircraft carriers; and Japan has got round constitutional restraints on military spending by sharply increasing the budget of the Coastguard. Fear of conflict drives this investment in a continent with a number of potential flashpoints. Emmott identifies five: the Sino-Indian border and Tibet; the Korean peninsula; the East China Sea; Taiwan; and Pakistan.

Both China and India have claims on the other's territory, the first on Arunachal Pradesh, the second on Aksai Chin. In addition, India affords asylum to the Dalai Lama, whom Beijing accuses of inciting recent rioting in Lhasa. The quandary on the Korean peninsula is the impossibility of assessing the future of the North's regime; its sudden collapse might tempt China to intervene, thus provoking confrontation with the South.

In the East China Sea, Japan and China are competing for rights to drill for oil and gas based on what each considers to be its exclusive economic zone; the dispute is symbolised by rival claims to the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. Over Taiwan, tension with Beijing has eased following the victory of the Kuomintang in both parliamentary and presidential elections, although no serious politician on the island can accede to the mainland's demands for reunification while it remains a dictatorship.

As for Pakistan, the uneasy relationship between the president and the parliament, the open defiance of Islamabad by jihadis in the tribal areas and Baluchistan, the limited authority of the Afghan president within his own country and the lack of progress in talks with India leave that nuclear-armed country as volatile as ever.

Emmott concludes his book with nine recommendations for preventing conflict in Asia. Among them are increasing the veto-wielding members of the Security Council to include India, Japan and various other countries, and similar reform of the G8, which excludes China and India. Within the region, the author suggests that the East Asia Summit, which was launched in 2005 and embraces East Asia, South-East Asia, India, Australia and New Zealand, is the best forum for confidence-building.

Japan, he writes, needs to follow up repeated apologies for what happened in the 1930s and 1940s with a fundamental change of attitude towards that period. China, whose ambitions cause the most anxiety in Asia, would benefit from transparency in its decision-making and defence spending. And India's main weakness is a poor relationship with its South Asian neighbours - above all, Pakistan. Lastly, the United States retains a vital stabilising role in the region, which it should enhance by giving greater priority to the NPT and climate change and by remedying its neglect of South-East Asia.

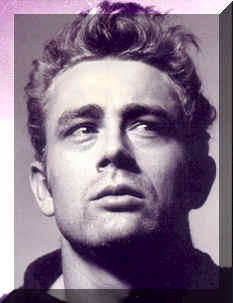

A former editor of The Economist and the author of six books on Japan, Emmott is a sensible and convivial guide through the minefield of intra-Asian rivalry. There are, however, several blemishes. Most seriously, he underplays the damage done to the NPT by the nuclear deal between Washington and New Delhi. To a lesser extent, the same applies to Japan's strategic concerns lest China invade Taiwan. I would not describe India's post-independence foreign policy as "isolationist"; it was a leading figure in the non-aligned movement and forged a close relationship with the

Soviet Union. And a fuller exploration of Chinese and Japanese attitudes towards the Yasukuni Shrine for the war-dead, the psychological core of differences between the two countries, would have been welcome. Finally, as a matter of fact, the number of US Marines stationed in Okinawa does not exceed that for American forces in South Korea; it is about half that figure.

Back to homepage